These are not places where you would see flowers growing

Who are the good people and the people that deserve it

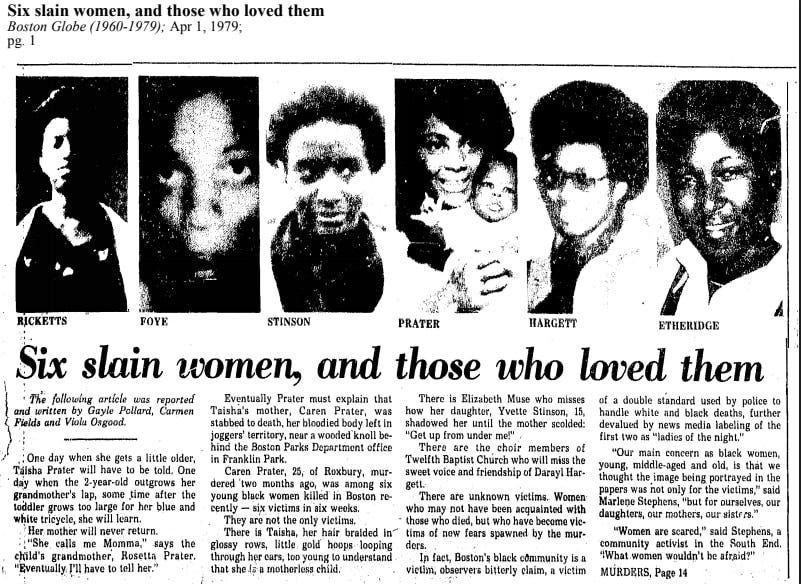

In late January of 1979 two young women including Andrea Foye who was seventeen and her friend Christine Ricketts who was fifteen were found strangled to death on the streets of Roxbury in Boston. The next day Gwendolyn Stinson who was also fifteen was found strangled as well. At first the press and police didn’t pay too much attention to the deaths due to they were black it is easy to imagine although I can’t say that for sure who can know what is in someone’s heart is something people say a lot.

Boston was going through a period of sharp racial tension which is the name for America but it was worse even than normal at the time with fallout from the school desegregation decision a few years before making for a particularly hostile cultural climate which is the name for America. The point is when you think about Boston and Boston being racist is probably one of the first things you think about this is the specific era you are thinking about not that it started the issue or ended it by any means but this was Boston at its most Boston.

When the first two girls were found the Boston Globe ran a story headlined: “Two bodies found in a trash bag.”

When one of the the girls’ mother went to the police to report her daughter missing a couple of weeks before she was found they didn’t seem interested in filing a report. She had probably run off with a pimp they told her according to a pamphlet titled “Six Black Women: Why Did they die?” that was circulated around that time by the queer black feminist socialist group the Combahee River Collective.

By then the number of murdered black women had grown to six which was enough murders finally for the Boston Globe to start really paying attention on April 1 of that year. That same day around a thousand people organized by community groups and concerned citizens and black leaders marched from the neighborhood where the girls had been killed — all within the same two mile radius in Roxbury, Dorchester and the South End— and walked through the streets shouting who’s killing us?

By the time the journal Radical America had reprinted the pamphlet the number six had been crossed out and replaced with a seven in the title and the seven had been crossed out and replaced with an eight and then by the end May the number had grown to twelve with eleven black women and one white woman killed.

At the marches around the time some of the black leaders in the community mostly men of course attempted to address the problem. This is racial violence they said.

“In the Black community the murders have often been talked about as solely racial or racist crimes,” the Combahee River Collective authors wrote in response. “It’s true that the police and media response has been typically racist. It’s true that the victims were all Black and that Black people have always been targets of racist violence in this society, but they were also all women,” they wrote.

“Our sisters died because they were women just as surely as they died because they were Black. If the murders were only racial, young teen-age boys and older Black men might also have been the unfortunate victims. They might now be petrified to walk the streets as women have always been.”

While they didn’t coin the term, the Collective were among the first to begin to outline the concept of intersectionality.

Further pushing back on the rhetoric from the community at the time that women shouldn’t go out alone in public without a man, they questioned whether or not it’s a man’s job to protect women in the first place, neither a practical or a just response as they wrote. A man cannot be their shadow twenty four hours a day they said and what’s more women should learn to protect themselves be it through self-defense or organizing together.

“What men can do to ‘protect’ us is to check out the ways in which they put down and intimidate women in the streets and at home, to stop being verbally and physically abusive to us and to tell men they know who mistreat women to stop it and stop it quick.”

I didn’t know anything about these women being killed but not many people around here do as Kendra Hicks, a community organizer, longtime activist, Boston native, and mixed-media artist told me. Hicks has been working on a series of installations called the Estuary Projects set up throughout the city at each place one of the women or girls was found. By doing so she hopes to remind people of what happened to them and to commemorate their lives.

“Helping us remember the apocalypse is the first function of the installations,” Hicks explains on her site. “Our ancestors have experienced and survived the end of the world. From those ashes, they’ve imagined and helped create the world they knew we deserved. Our ability to locate ourselves in our history will aid us in flexing the muscles of our imagination.”

I hadn’t heard of these murders until I came across your project. Are they widely known?

I didn’t know about it growing up either. Like a lot of things it’s just part of history, and in Boston in particular it’s really easy to forget about things like that. I think we’re a city of niceties so things like this kind of get swept under the rug a lot. In particular there’s something to be said about the fact that these were women and black women and that relates to how their stories were not being told. Everybody knows the story of the man who murdered his pregnant wife in Roxbury and blamed it on this phantom black man but no one knows this story.

What sorts of pieces have you been putting up around the city?

We’re mostly using I guess you would call them synthetic carnations. The carnation in particular is seen as the flower of women, but also in Greek mythology and Christianity, the carnation inception, how it came to be on the earth, stems from the pain of a woman. In the Bible when they say Jesus was being carried to the cross his mother Mary was weeping and her tears hit the ground and that’s where the carnation came from. It’s a spiritual flower and I wanted to use them in all the installations. The other symbolism behind the flower, particularly where I’m putting them, these are not places where you would see flowers growing. There’s something I’m trying to signal to: things that grow and are successful and thrive in places where they’re not to supposed as a way of looking at our communities.

2019 feels like the end of the world. We have Donald Trump and family separation and all these issues. What I’m trying to point to is we’ve actually experienced the end of the world many times and survived and thrived.

What has the reception been like?

I think people are overwhelmed by the story and the magnitude of it and the fact they didn’t know about it happening at these places they walk by every day… The surviving families members of the women, they feel like their family members haven’t been forgotten. Most of the victims’ cases went cold and the people who murdered these women were never arrested.

How many were killed that year?

Eleven women, but there are ten installations. The first victims who were best friends were murdered together. It wasn’t until I did a lot of research and found that twelve women were murdered in that three month period and the last woman was a white woman. And that was the only death that garnered national attention. Once she was murdered it became this thing, when in reality black women were being murdered before that.

Did any of their stories in particular resonate with you?

You know I think the thing that stuck out to me about the stories was how different they were. If I wanted to relay anything about these women it’s that they came from so many walks of life, from fifteen to thirty four years old. From sex workers to women who sang at the church choir. I think that in itself is a story. What’s it mean that black women are disposable when you think about respectability and what does that mean? Who are the good people and the people that “deserve it”? They were so different and it didn’t matter what they had decided to do with their lives. Whatever the culture, the level of systemic oppression against black women made them ok to kill. By whoever. It could’ve been eleven different people. I think that’s really at the core of the story.

How many got solved?

I don’t know exactly but I want to say like three. The supermajority went unsolved.

Boston has a very bad reputation for racism but I think it’s more personal racism than systemic that people talk about. How do you see it now?

I think it’s gotten better in some places, then it’s also as bad as it ever was and worse in others. I think the trick we play on ourselves in Boston that allows it to go underground is to say it’s not as bad here. It kind of lets us ignore it when we see it. I worked in city government for a while, and Boston as a city is a model for so many different places. I worked at the Public Health Department and places all around the country want to talk about how Boston is doing racial equality work. The work we were doing there was front of the line, but that doesn’t mean it translates into people’s lives. We were naming structural racism as a social determinate of health before others were doing it. I was a street worker for four years. The street worker program was started in Boston in 1995. It’s like youth workers on steroids. They work with young men women who are gang involved doing direct intervention. The interrupters in Chicago were modeled after that plan in Boston. I traveled to Bermuda to help get it set up there. In 1996 we had the Boston Miracle where we went the entire year without a murder.

Just like anywhere else if you tell yourself you’re doing better than anywhere else you ignore your own problems. All the people in Boston who have been murdered by the police have only been black. These are things we haven’t gotten away from.

Thousands of teachers from the Denver school district and many of their students participated in a strike on Monday. The teachers whose job is obviously very easy as every knows are striking in protest of low and unstable salaries that are often tied to bonuses that they say are unpredictable and unfair. Rising costs of living in Denver like everywhere else and in inability to know ahead of time how much they are actually going to make in some cases has led to many teachers in the city being forced to take on second jobs in order to survive.

Hayley Breden a high school social studies teacher was among the many to walk out today. She and her co-workers marched to the steps of the state Capitol where she estimated about 5,000 teachers, students, and members of the community gathered in support. I asked her what the issues behind the strike were and what they were hoping to see change.

How do you feel?

At my school this morning the students had a walkout at 8 am. It was organized ahead of time and permitted, and they joined us on the picket line for an hour. That was really motivating. I have several students who want to become teachers so they’re worried about not getting paid much. It’s important for them to see us working to make the profession sustainable so they don’t have to take a higher paying job that they don’t necessarily want to do. That was the best part of the day for me.

What is the key issue?

In Denver we have two contracts. One deals with class size and planning time and other working and learning conditions and that is up for negotiations in 2022. But the one now is all about compensation and the merit-based pay system we have. What we’re hoping to achieve is more money towards base salary and no bonuses or incentive pay. Since a chunk of our pay is bonus pay it’s pretty unpredictable. Two years ago my school got three different base pay incentive chunks and this year we received zero because the number of free and reduced lunch student at my school changed. If we had fourteen more we would’ve received a bonus from the district. Other bonuses depend on things like test scores. It’s very unreliable which ones we’re going to get or not get. We want people to be able predict their salaries.

I certainly doin’t think this but people seem to want to argue sometimes that incentive bonuses motivate teachers.

I’m sure there are a handful of teachers who maybe are motivated by bonuses, but as a teacher I’m motivated to work hard because it’s the right thing to do. I would be doing a disservice to my students and society if I wasn’t working hard. The students’ futures and my coworkers and excellent administrators are what inspire me to work my hardest not some $800 I may or may not get. I think it’s insulting to assume a teacher would only do their best if they were going to get a bonus.

Another thing is that a lot of the schools in Denver — high priority schools with a high percentage of students of color and lots of free and reduced lunch students — are the schools that do get a lot of these incentives. But their turnover rates are some of the worst in the district. So the argument that bonuses keep teachers at these school isn’t a fair one.

Have you been able to use this as a teachable lesson for your students?

Yes, definitely. In my U.S. history class we did some learning about different strikes and aspects of the labor movement in the late 1800s. I think it was helpful for them to understand what a strike is, how they’re planned, and how people really don’t want to go on strike but sometimes that’s the only available option.

I read that Denver had an opportunity to vote for higher taxes on families earning over $150,000 last year and the money would’ve gone to schools, but it was voted down?

There was a statewide ballot initiative that would’ve amended the Constitution called amendment 73. Since it was statewide it failed but it would’ve allowed more money for education and teacher pay statewide. Denver County actually voted to support that but the rest of the state did not. Had that passed we probably wouldn’t have gone on strike. While Denver voters voted in favor mostly of 73, the rest of the state didn’t so much.

There is this persistent attitude that public school teachers have an easy and cushy job.

I think one thing that’s difficult maybe for people to understand is that since everyone has been to public school they all assume they know what teaching in public school is like. Which is wonderful, public school is the only institution that serves everyone everywhere. That’s great. But I think sometimes people think they understand things that are not accurate, or they’ve had their own experience but it might be very different form the current reality depending on where and when they went.

There’s been quite a few teacher strikes around the country. Did that inspire your union?

A couple of the folks in union leadership and I had a video call with some teachers from Los Angeles last week to share strategies. Mostly it was really empowering and rejuvenating for us to talk to teachers who had just come off a strike. There’s a lot of communication and solidarity and support right now.

What do you expect is going to happen next?

There’s bargaining again tomorrow. Hopefully after seeing what happened in the school today — one of the local public radio reporters shared a video of one of the high schools and her words were ‘not a lot of learning took place’, because once the students figured out there were no teachers they decided to walk out in support of us. I think after today the school district will have a different idea on negotiation. We’re hoping to have this wrapped up by then.

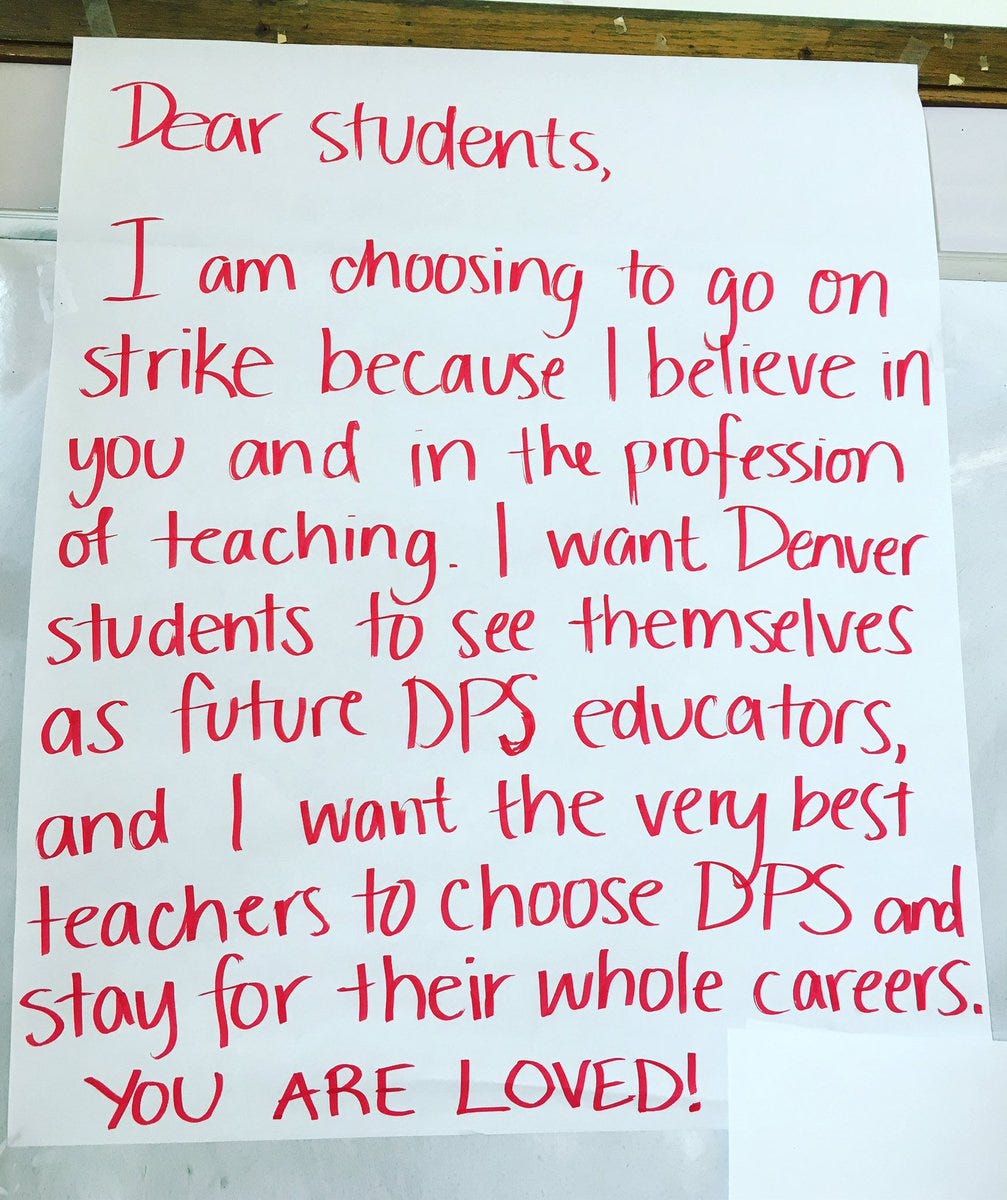

You shared a sign on Twitter you left for your students on Friday. What was the message there?

This strike is only about our compensation contract, it’s about pay only, but really it’s about more than that so I wanted them to understand why paying teachers a competitive salary with neighboring districts is really important. The kids who are seniors now, maybe a third of their teachers have left since they were freshman. If they’re wondering ‘Why aren’t any of my teachers at my graduation?’ I want them to understand why and to know we’re trying to fix that.