Greg Ginn said he would press the Black Flag record himself.

And just like that I have exhausted my capacity for analogizing Mrs Dalloway to hardcore punk bands. Uh… they both spend all day wondering how the party is going to go later that night and thinking about a girl they kissed one time (?)

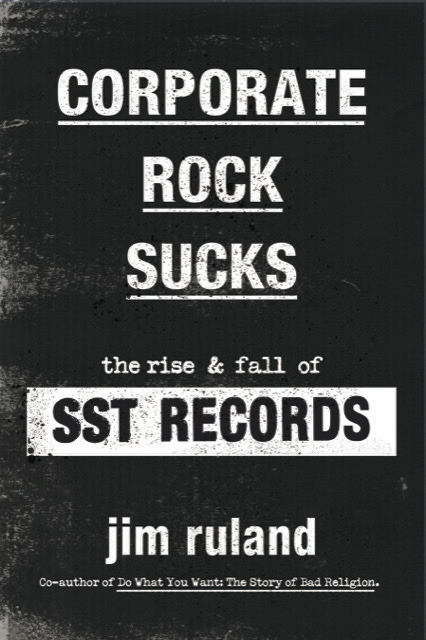

That decision of Ginn’s is the lynchpin for the story I’m sharing here today. It comes from a great new book called Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise and Fall of SST Records written by veteran music journalist Jim Ruland which you can purchase here if you like.

Music fans will of course know SST Records as the one time home to legendary bands like Minutemen, Hüsker Dü, Bad Brains, Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr, Screaming Trees, Soundgarden and many others.

As the marketing materials I’m copying from here say SST “was the most popular indie label by the mid-80s–until a tsunami of legal jeopardy, financial peril, and dysfunctional management brought the empire tumbling down. Throughout this investigative deep-dive, Ruland leads readers through SST’s tumultuous history and epic catalog.”

As most of you will know Hell World turns into a music publication from time to time in part because it’s good for both myself and the readers to take a break from staring into the hole in the earth and in part because I spent the bulk of my early career as a music journalist and I occasionally miss it. Very occasionally.

Speaking of two of those aforementioned SST bands you may enjoy these pieces if you never read them that I wrote after the passing of Mark Lanegan and Chris Cornell.

Both are behind the paywall but you can grab a nice little discount here.

Subscribe today for a year of Hell World and you’ll also get a six months paid subscription to Foreign Exchanges by Derek Davidson and Forever Wars by Spencer Ackerman included. Please reply and let me know and I’ll set it up.

Real quick before we get to the book excerpt though:

I somehow just found a page on my Substack dashboard that is maybe new or maybe I just never saw that has a couple dozen messages from people that I guess the software prompts you to write when you don’t want to or can’t pay for this anymore. I’m sorry I never responded because I had no idea they were there and most of them are so nice! There’s a lot of I love reading this but I am simply broke right now and I hope to be back. Some are like this shit is too depressing I can’t handle it. Others are like I don’t want to give any of my money to Substack anymore.

Stay tuned for some news on that front soon.

Ok here’s the book thing. Stick around for a bit more from me down below.

SST vs. Bomp! The end of the ’70s

1

Greg Ginn was frustrated.

The Hermosa Beach guitarist had spent the better part of two years pouring his heart and soul into his band—a noisy quartet called Panic!—and had nothing to shor it. Panic! was faster than the Stooges and heavier than Black Sabbath. The band had its own gear, rehearsed in its own practice space, and wrote its own material, which was part of the problem because venues wouldn’t book new bands that played original music. From the clubs in Hollywood to the bars along Pacific Coast Highway, bookers were looking for musicians who could play Top 40 hits. “I thought of music as kind of a scam,” Ginn said.

Ginn didn’t get into music until he checked out the action at the Lighthouse—a nightclub down the street from his parents’ house that happened to be the most important venue for jazz music on the West Coast. Ginn played guitar during breaks from his studies at UCLA, but after seeing the Ramones play at the Roxy Theatre in the summer of ’76, all he wanted to do was make his own noise.

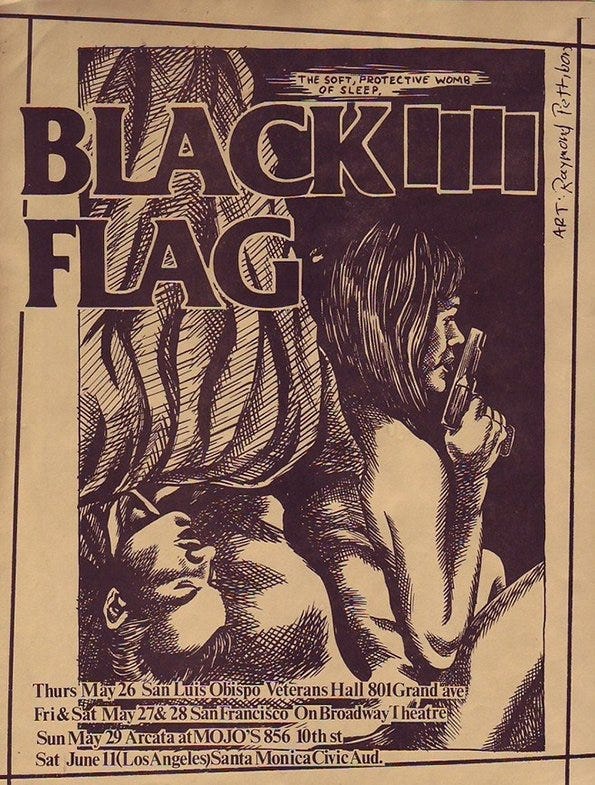

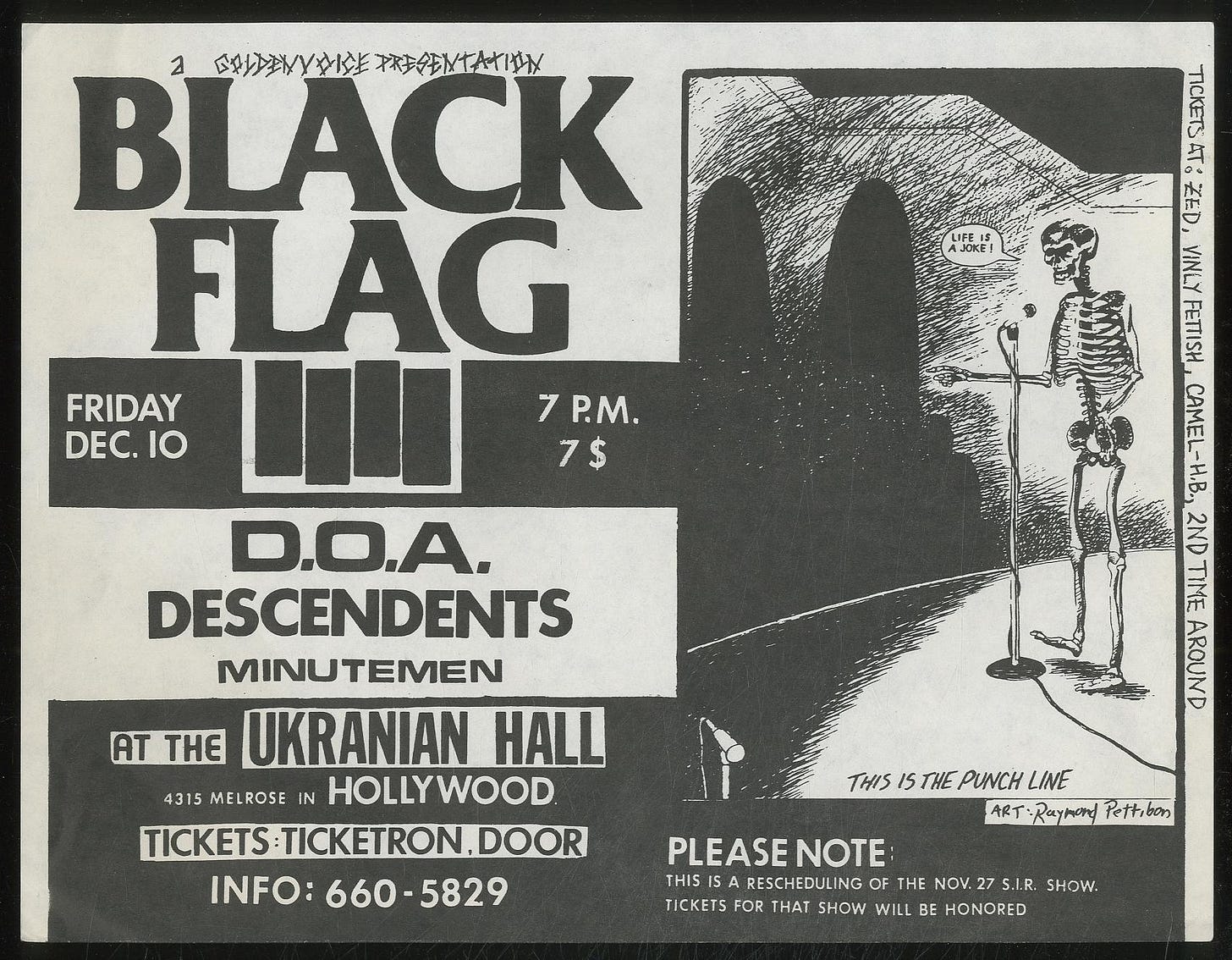

Ginn started writing songs—both the music and the lyrics. It took him a while to find people who were as serious about being in a band as he was. His younger brother Raymond struggled through the songs on bass guitar, but he wasn’t a musician. He had his own ambitions as a visual artist and christened himself with the pen name Raymond Pettibon. Ginn’s abrasive yet commanding style developed from not being able to rely on other players. “I was doing songs that could be held down by lead guitar,” Ginn said.

Ginn found his singer, Keith Morris, at the local record store. Morris knew a rock and roll drummer named Bryan Migdol, the younger brother of a close friend who’d died in a car accident. They started jamming in Ginn’s garage. Things began to click when Gary McDaniel of Würm took over on bass. McDaniel, who would change his name to Chuck Dukowski, let them use his band’s practice space in an abandoned bathhouse on the Strand dubbed “the Würmhole.”

The Hermosa Beach police decided this was too much excitement and kicked everyone out. Ginn rented a space in a strip mall on Aviation Boulevard, not far from one of the bait and tackle shops Morris’s father owned and operated. The band went back to work, conducting marathon practice sessions that lasted late into the night and occasionally attracted crowds of friends. When the calendar flipped from 1977 to 1978, Panic! still hadn’t played a single show, which was becoming a source of frustration.

Panic! participated in the burgeoning punk scene that had taken root in Hollywood and was spreading to every corner of Southern California. Morris even made the drive up to San Francisco to see Johnny Rotten detonate the Sex Pistols at Winterland. Despite the band’s engagement in the scene, Panic! Was spurned by Hollywood punks. “They considered us to be nothing more than beach rats,” Morris said. “If they were competing in the Sid Vicious lookalike contest, we were competing in the Peter Frampton lookalike contest. That didn’t sit well with a lot of those people.”

The band’s appearance defied fashion-conscious Hollywood insiders and helped define its own aesthetic. The members of Panic! didn’t dress up to go to punk rock shows or to play gigs. They wore the same clothes on stage as they wore when rehearsing or going to work. This translated to a lack of opportunities in Hollywood. “There was a kind of anti-suburban vibe in the early LA punk culture,” Dukowski said. Ginn believed the best way to get people to take his band seriously was to put out a record. Panic! couldn’t get a gig because it didn’t have a record, but how do you get a record deal when you’ve never played a show?

Glen “Spot” Lockett, a recent transplant to Hermosa Beach who worked at the Garden of Eden vegetarian restaurant where Ginn frequently ate lunch, offered a solution. “I was writing for the Easy Reader and doing music reviews,” Spot said, “and one day he was eating there and he kind of called me out on one of the reviews I wrote. So we got into a discussion, talking about this stuff.”

Ginn and Spot learned they had a great deal in common. They were passionate guitar players, and both of their fathers were military aviators who’d flown combat missions overseas during World War II. Ginn’s father, Regis, served as a navigator with the US Eighth Army Air Corps in England. Spot’s father was a member of the famed Tuskegee Airmen: the first Black aviators of the US Army Air Corps.

Spot suggested that Ginn record at Media Art, an art complex with a darkroom where Spot developed his photos and a recording studio where he recently started working as a sound engineer. Best of all, it was right down the street. Ginn said he would look into it. Spot didn’t know how serious Ginn was, but he would soon find out.

Panic! assembled at the studio late one night (when the rates were cheapest) and recorded eight songs—all originals. Because the songs were so short, it wasn’t nearly enough material for an album, but more than enough for an EP. The record was engineered by Dave Tarling with assistance from Spot. It was the first of many projects Spot would have a hand in making with Ginn. Panic! sent a tape of the recording to Bomp! Records and received a favorable response: Greg Shaw was interested in signing the band and offered to put out the EP.

Things were finally moving forward, but the band was in a near-constant state of flux. Bryan Migdol parted company with Panic!, and Ginn put an ad in the paper for a new drummer. Roberto “Robo” Valverde responded and immediately started rehearsing. In September, Bomp! sent Panic! a recording contract for the eight songs. Ginn crossed off four of them—“No Values,” “White Minority,” “I Don’t Care,” and “Gimme Gimme Gimme”—and in an accompanying letter indicated his preference for “Nervous Breakdown” to appear on Side A with “Fix Me,” “I’ve Had It,” and “Wasted” on the flip side. Ginn wasn’t worried about the brevity of the songs. “I was rebelling against these people who try to establish their manhood by composing prog rock opuses,” Ginn said. “My goal was to create a concise listening experience.”

Ginn promised to send photographs to help promote the record, which he did the following month. Ginn’s correspondence with Shaw was typed on stationery for SST Electronics, his mail-order company, and signed “Gregory Ginn.”

More changes were afoot, this time involving the band’s name. Pettibon caught wind of another band with the same handle. “I remember telling my brother, ‘There’s already this band named Panic from England,’” Pettibon said. “‘Maybe it’s not a good idea to have the same name as some other band.’”

This created an opportunity to rename the band. Morris recalled Ginn wanted to call the band Rope, which he wasn’t too thrilled about. Pettibon had another idea. He suggested Black Flag, which conjured up a number of associations: It was both a symbol of anarchy and of piracy on the high seas. Black Flag was also the name of a popular insecticide. But it was Pettibon’s simple but innovative logo that sealed the deal: four staggered vertical bars forming a stylized flag rippling in the wind; individually, they resembled the pistons of an engine. Ginn took it and ran with it.

With a new drummer, a new name, and a new logo, Black Flag was ready to go, but Bomp! was slow to respond. Pettibon suspected Shaw wasn’t in favor of the name change. After months of delays, Ginn considered putting out the EP himself, but he didn’t know anything about making records. He did, however, know of another band in Hermosa Beach—a pop-infused garage band called the Last—and he decided to give them a call.

2

The early punk rock records made in Los Angeles were few and far between, pebbles cast into an ocean of corporate-controlled rock and roll, but even the smallest stone creates a ripple.

In July 1977, the Germs released what many regard as the first LA punk record. The band recorded the single “Forming” in Pat Smear’s garage on a reel‑to‑reel recorder. Chris Ashford, a friend of the band, volunteered to help the Germs put out the record. As the night manager at Peaches Records and Tapes on Hollywood Boulevard, Ashford knew a lot of people in—or at least adjacent to—the music industry, but he didn’t know anything about pressing a record. Through his experience at Peaches, Ashford knew that Rhino Records released novelty and compilation records under its own imprint, so he went to Richard Foos at Rhino for advice. Foos recommended that Ashford take his project to Monarch Record Manufacturing Company on West Jefferson Boulevard in West LA.

Ashford was in business. He chose the name What Records? for his label and pressed one thousand copies of the Germs’ debut at Monarch. “Forming” was backed with a live recording of “Sex Boy” at the Roxy Theatre from the night the Germs auditioned for the Battle of the Bands sequence in Cheech and Chong’s Up in Smoke. “We never had any idea that it would ever amount to anything,” Ashford said. “We got onto this thing the universe put us into and it kind of took off.”

Through his contacts at Peaches, Ashford got the record to new fanzines, like Slash and Flipside, cropping up around town. Despite the crude quality of both the recording and the musicianship—or perhaps because of it—“Forming” caught the attention of the underground punk press. The bemused review by Claude Bessy (a.k.a. Kickboy Face) in Slash helped spread the word about this noisy, rambunctious band. “First of the hard-core LA groups to come up with a single, the Germs have recorded (I think that’s the word) one of the most mind-boggling songs I’ve ever heard. They take monotony to new heights and push the absurdity factor further than almost any other group.”

Not everyone liked the record. “We gave the single to Back Door Man,” Ashford recalled, “and they hated it. We just took that as, ‘This is great. We’re getting bad reviews here, bad reviews there. It’s selling the record.’” Back Door Man was an influential rock zine run by Phast Phreddie Patterson and Don Waller out of Torrance in LA’s South Bay. Back Door Man’s writers took a hard stance against soft rock and roll with screeds from the first generation of LA music writers. Although Back Door Man wasn’t a punk zine, the editors covered it with cautious enthusiasm and even included a centerfold poster of Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols in the March/April 1978 issue.

Despite its mixed reviews, Greg Shaw of Bomp! Records took an interest in “Forming.” Bomp! had its roots in the spirited underground music zine Who Put the Bomp, which he and his wife Suzy founded in 1970. Who Put the Bomp helped launch the writing careers of Lester Bangs of San Diego, Greil Marcus of San Francisco, and Richard Meltzer of New York, and it ran until November 1979.

Who Put the Bomp reflected Greg and Suzy Shaw’s passion for rock and roll: how it was made, played, written about, and celebrated. They sought to start a conversation about the music they loved that had little to do with access to the musicians or even the industry itself. The Shaws viewed punk as the latest manifestation of ’60s garage rock and psychedelic music, and they were early champions of the LA punk scene. Bomp! distributed the Germs’ debut single along with the Dils’ “I Hate the Rich,” which was issued in September 1977. Both singles hit Record World’s New Wave Chart. Although What? would go on to release records by other early LA punk bands like the Eyes, the Skulls, and the Controllers, Ashford didn’t regard it as a proper business. He had been inspired to make records the way others were motivated to pick up instruments, take photographs, or create zines. It was his way of participating in the scene. The notion of creating a commercial enterprise came after the fact, if it came at all.

Still, that a crudely recorded single by a band many didn’t take all that seriously could catch the attention of fringe elements of the media and register a minor blip in the music industry demonstrates how ready LA was to shake up the status quo. For Ashford, it was a matter of being at the right place at the right time. The Masque, the practice and performance space in the basement of the Pussycat Theatre that served as ground zero for the early LA punk scene, was right next door to Peaches.

Hyperbolic descriptions of punk rock shows in Slash lent a mirage-like quality to the scene, another overhyped manifestation of the LA dream machine. But watching the Germs play at the Masque and then seeing the band’s single in the bins at Peaches alongside records by the Sex Pistols and the Ramones galvanized scores of people to start their own bands and create their own labels. The release of “Forming” in the summer of ’77 sent a message that a local band could make a record and be recognized for it—and you didn’t even have to know how to play your instruments.

As bands proliferated like bacteria in a petri dish, it didn’t take long for indie labels to start popping up around LA. Dangerhouse Records and Posh Boy Records issued releases the following year. Slash got into the game with the first EP from Slash Records: Lexicon Devil, also by the Germs. In 1977, Bomp! released Destroy All Music, the first EP by the Weirdos, who were arguably LA’s most popular punk rock band at the time.

These labels bolstered the fractious scene and proved that punk rock was more than fucked‑up kids with blue hair playing dress‑up with the dregs of Hollywood’s faded grandeur. They provided the oxygen the scene needed to breathe and enabled bands to break through the barriers imposed by the record industry. Without these labels, there’d be scores of bands like the Screamers who flamed out without leaving a proper, band-sanctioned release as vinyl proof of its white-hot existence. These labels operated for reasons that had nothing to do with the rock and roll fantasy of getting rich and famous: to make art, to document the scene, to create something new and in doing so prove that anyone could do it.

3

It was a bad time for rock and roll. If the government wanted to ban kids from forming rock bands, it couldn’t have gone about it any more effectively than the music industry did in the 1970s.

After World War II forced big bands to downsize, rhythm and blues began to flourish. While New York and Memphis both claim to be the cradle of rock and roll, no city had more record labels than LA, where R&B, gospel, and Latin bands played to packed houses, often sharing the same stage.

In postwar America, the radio disc jockeys who brought these new sounds to the public had an enormous influence. In cities big and small, the most popular DJs were bona fide celebrities. They were personalities who made regular appearances at dance halls and nightclubs and were frequent guests on local television shows. In the song-based music industry, if a DJ liked your single, they’d play it on the radio and listeners would buy it. Sometimes these DJs had a hand in getting bands booked for a showcase or a matinee performance sponsored by the station. In this culture, hundreds of bands thrived in cities across the country, and the best of them broke through to the national stage. It was a flawed system that often exploited songwriters, but with a mix of luck, pluck, talent, and perseverance, bands could make the leap from garages to the airwaves.

Then everything changed. When the dust settled after the payola scandal—the practice of rewarding disc jockeys with cash, gifts, and even royalties in exchange for airplay—radio stations took the power away from their DJs and started negotiating with the labels themselves. The record labels worked with program managers to ensure that only predetermined “hits” were broadcast. People in suits dictated the songs that would get the most airplay and inserted commercials at regular intervals, which also generated income from corporations that wanted to reach their target audiences. Gone were the days of DJs spinning whatever records they wanted, whenever they wanted, for as long as they wanted. Welcome to corporate rock and roll.

Naturally, the commercialization of radio favored national touring acts over regional bands. It no longer mattered what was happening in New York, Chicago, Miami, or Los Angeles. All across the country, everyone was listening to the same thing. This environment eschewed risks and put a premium on appealing to the greatest number of people, dumbing down the music and paving the way for easy listening, a genre of music so innocuous that no one could possibly be offended by it.

As the public’s listening habits changed, the venues that featured live music acted accordingly. They stopped booking local bands that played original music. For musicians in the ’70s, there were plenty of opportunities to perform—as long as they played other people’s music. For artists with something to say, there were far fewer outlets for creative expression than there had been just a decade before.

This shift was felt in the large sprawling exurbs of major American cities. Bars and nightclub owners who featured live music insisted their acts play covers of Top 40 hits. Sometimes a booker would give a local band a chance, only to get cold feet when the audience complained. It was a frustrating time for musicians, and the South Bay was an archetype of this dynamic.

The South Bay wasn’t your typical suburb but a densely packed network of sub-cities that stretched from Los Angeles International Airport to the Palos Verdes Peninsula. Suburbs, by definition, are urban-adjacent bedroom communities where people live but don’t work. The post-suburban “edge cities” of the South Bay were entirely self-contained, with jobs, schools, stores, industry, and clusters of single-family residences all packed together. The suburbs of the twentieth century were defined by movement from place to place, but in post-suburban America you could find everything you needed within a few square miles. Nowhere was this truer than in LA, a city without a center and with more single-family residences than anywhere else in the country.

The southwest corner of Los Angeles County sits on parts of Santa Monica Bay, the Pacific Ocean, and San Pedro Bay, and is home to the Port of Los Angeles, which is still the busiest port in the country. After World War II, the South Bay became headquarters for the burgeoning aerospace industry with its many links to the military and defense. The Beach Cities were also the playground of world-class surfers like Dewey Weber and Greg Noll and played an important role in the popularization of skateboarding and roller skating. Yet this same region was once home to a dynamic music scene.

In the ’60s, the South Bay was known for its jazz clubs, coffee shops, and bars where one could hear the latest sounds in bebop, folk, and psychedelic rock. But by the mid-1970s, this was no longer the case. The sounds coming out of the clubs were as uniform as those on the FM dial. This was especially frustrating for songwriters and musicians in the South Bay because of its proximity to Hollywood, the heart of the music business. These were dark days for musicians who wanted to play their own material. Either you fell in line or found something else do. For Joe Nolte, neither option was acceptable.

4

Joe Nolte wrote songs, sang, and played guitar with his brothers Mike and David in a Hermosa Beach band called the Last. They played an unclassifiable blend of neo-psychedelic pop and up‑tempo garage rock to create a sound as all-American as the Beach Boys—who, despite revolutionizing surf music, were actually from Hawthorne, several miles inland. Unfortunately, there was nowhere to play. “It was a closed circuit,” Joe explained. “There was no way in, especially if you wanted to play rock and roll because you’d be dead. We’d let this rebellious music roll over and die with a whimper.”

Joe was no stranger to the Hollywood punk experiment. After reading about New York bands like Television, Blondie, and the Ramones, he sought out this new genre of music and liked what he found. Like Shaw, he saw punk as rock and roll’s best hope, and he was determined to be part of it. Joe and his brothers regularly attended shows at the Masque and badgered the proprietor, Brendan Mullen, to book them, but they weren’t having much luck.

Joe decided to do what other independent-minded bands were doing and put out a record. He didn’t have to look to Hollywood for insight; he found inspiration much closer to home. Back Door Man was now putting out records through its own imprint. Earlier that year Back Door Man had released a seven-inch single of “He’s a Rebel” backed with “You’re So Strange” by the Zippers, a power pop band with big hooks and a jagged sound whose members were from all over the South Bay.

When it was time to make a record, Joe turned to his bandmate Vitus Mataré, who played keyboards and the flute but also had a passion for recording. Mataré’s mother was a classical harpsichordist who had a two-track recorder and a pair of microphones. Mataré had recorded the Last once before: a song called “Light Another Candle” at Randy Neece’s house in Brentwood. Neece, an acquaintance of Mataré’s, had performed in the Young Americans, an internationally acclaimed show choir whose image was as wholesome as its name. Neece was always encouraging Mataré and his bandmates to write and record their own music.

Mataré asked Neece to sing on a song and help them record. Neece agreed, but when they realized they needed another guitar, they turned for help to Neece’s neighbor, who happened to be the Eagles’ guitarist Joe Walsh. Not only did Walsh lend them a Les Paul guitar and a combo amp for the recording, but he also offered to run a mic cable from his house to Neece’s. “The coolest dude ever,” Mataré recalled.

In the fall of 1977, the members of the Last gathered at the band’s practice space at Scream Studios in the Valley to record the backing tracks. Then they convened at Mataré’s mother’s house in Brentwood, where he’d set up a home recording studio in the pool house. The Last recorded eight songs before Joe’s amp caught fire. “His amp shorted out and was smoldering,” Mataré said. “I carried it out to the backyard and dropped it into my mother’s pool.”

For its first single, the Last settled on “She Don’t Know Why I’m Here” backed with the Clash-inspired “Bombing of London.” Mataré consulted with Neece, who suggested they get the recordings mastered by Hank Waring at Quad Teck and pressed at Alberti Record Manufacturing Company in Monterey Park. Mataré took heed of Neece’s advice, and on November 7, 1977, three hundred copies of the Last’s debut single were ready to be picked up. They called the label Backlash.

Joe dropped off personalized copies of “She Don’t Know Why I’m Here” with Kim Fowley, who organized a series of New Wave Nights at the Whisky; Mullen at the Masque; Patterson and Waller at Back Door Man; and Shaw at Bomp! Records. Lisa Fancher, who worked at Bomp! and went on to start Frontier Records, loved the single: “I still think it’s one of the greatest LA songs ever,” Fancher said. “It gives you a feeling like the Modern Lovers when they sing about Massachusetts. ‘She Don’t Know Why I’m Here’ is just an absolute classic.”

The Nolte brothers had written enough songs for an LP, and they hoped their single would catch the eye of someone willing to put it out. Joe and David were at the Masque one night when a triumvirate of tastemakers—Patterson, Mullen, and Shaw—told Joe they’d listened to the record and liked it. In his enthusiasm, Shaw expressed interest in releasing it. Joe was overjoyed. “It was the culmination of what I wanted for so long,” he said. “It was insane!” David was a bit more circumspect: “Greg might have said, ‘Yeah, I want to put out a record by you,’ but I think he said that to a lot of people.”

The Last’s fusion of ’60s garage rock and ’70s pop was perfectly suited to the label’s psychedelic sensibilities. On paper, Bomp! was the ideal home for the Last, but Shaw lacked the financial capital to follow through with his plans. “I think that was his nature,” David said, “not just with us, but with everybody he worked with back then. That was part of what he did. Just Greg being Greg.”

Shaw wanted to re‑press “She Don’t Know Why I’m Here” on the Bomp! label and bought out all of the remaining copies of the single. What had seemed like a demonstration of the label’s good intentions struck the band as a bad move once Bomp! began to drag its feet. As the days turned into weeks and the weeks turned into months, the Last was playing more shows but didn’t have any records to sell.

In June, the Last went back to Alberti to press the band’s second release: “Every Summer Day,” an homage to the Beach Boys that name-checks Hermosa Beach in the lyrics. The Last’s new record helped get the band noticed around Los Angeles, including in its hometown. In the fall of 1978, David answered the phone and Ginn was on the line. He wanted to talk to Joe about the Last, but Joe was at work, so he spoke with David instead.

David had heard about Panic! from Bill Stevenson, his classmate at Mira Costa High School. Although Bill was a grade lower than David, they were enrolled in the same Spanish class. Stevenson was an avid fisherman, and he knew the band’s singer through the Hermosa Tackle Box, Morris’s father’s shop on Pier Avenue, which Stevenson had been going to since he was eight years old. “Within a few weeks of Bill telling me about Panic!,” David said, “Greg called the house to ask about the Last and how we put out our record. He said he had a thing going with Greg Shaw and was maybe going to do a deal with him to put out the Nervous Breakdown EP.”

David recalled they had a good conversation, and he shared his band’s experiences with Ginn: gigs they’d played, record stores that carried their music, and—most importantly—where they pressed their records. Although Ginn hadn’t completely soured on Shaw, he was exploring his options. “He was starting to get the sense that Shaw was promising the sky and couldn’t deliver,” David said.

The news that there was another punk rock band in town came as a welcome surprise to Joe, who believed Hermosa Beach’s “entire punk rock contingency could fit in my car.” David was trying to do something about that by turning his classmate on to punk rock. He made Stevenson tapes and finally had a breakthrough with Devo’s “Mongoloid.” David took Ginn up on his offer to come by the practice space on Aviation, and Stevenson and the Nolte brothers joined in on a jam session that included the Devo song, KISS’s “Love Gun,” and riffs that would eventually coalesce into Black Flag’s “Room 13.” For Stevenson, it was an earth-shattering experience: “That was when I realized, ‘Oh, you don’t have to play covers, you can play your own things that you come up with?’”

Over the course of this impromptu session, Greg Ginn and Joe Nolte discovered they had a lot in common. They shared their frustrations with the lack of opportunities to play in LA and the limitations imposed by the music industry, which now included Bomp! Both musicians were concerned that it was taking too long for the label to put out their records. “We needed to capitalize on the momentum of ‘She Don’t Know Why I’m Here’ by getting a record out,” Joe recalled. “Panic! is supposed to have their record released on Bomp! That didn’t come out either. So we’re both in a holding pattern. We’re frustrated as hell.”

Joe wasn’t going to let his opportunity to put out a record with Bomp! Slip away. He was determined to hold Shaw’s feet to the fire, even if it meant some unpleasantness. His patience was rewarded when Bomp! Records finally released the Last’s debut, L.A. Explosion!, the following year.

Ginn’s situation was different. Black Flag, which still hadn’t played its first show, didn’t have the Last’s track record. In addition, the Last’s pop-infused melodies on songs like “Every Summer Day” were at least palatable to bookers and promoters; Black Flag’s frenzied, ear-bashing chaos was not. In 1978, Black Flag was virtually unknown outside its small circle of friends in the Beach Cities. Joe briefly discussed with Ginn putting Nervous Breakdown out on Backlash. Ultimately, Ginn decided to follow the example of his Hermosa Beach neighbors and do it himself.

This was a crucial step for the growth of the band. It also proved to be a pivotal connection for countless Southern California punk and hardcore bands that followed Black Flag’s example and pressed their own records for decades to come—all thanks to an unlikely string of connections between the Last and Black Flag that went back to a forward-thinking song and dance man named Randy Neece.

Excerpted from CORPORATE ROCK SUCKS: The Rise and Fall of SST Records by Jim Ruland. Copyright © 2022. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Subscribe to Ruland’s newsletter Message from the Underworld here.

You will remember the video of police in Buffalo violently shoving an elderly man to the ground during the protests in the summer of 2020. In a shocking twist an arbiter hired by the city has clear the cops of any wrongdoing.

The Buffalo News reports:

Arbitrator Jeffrey M. Selchick said he found that Officers Aaron Torgalski and Robert McCabe did not violate Police Department regulations and did not intend to injure Martin Gugino during the protest outside City Hall on June 4, 2020.

Torgalski and McCabe testified before the arbitrator that they were trying to protect themselves and denied that they were trying to hurt Gugino during the protest.

The officers’ use of physical force was “absolutely legitimate,” wrote Selchick, who added that, in his analysis, Gugino was “definitely not an innocent bystander.”

The arbitrator said the officers testified that they were only trying to move Gugino out of their “personal space” and physically keep Gugino away from their weapons.

The arbiter said that the cops were scared the old man was getting close to his gun and also that one of them was scared he might catch Covid from him so the shove was necessary. The one other thing cops do besides lie is get scared. It’s very bad for all of us when either thing happens.

Here’s a good thread on the subject:

Look at this video of cops trying to pull over a driverless car in San Francisco. They don’t know what to do because there’s no one to shoot at or to pull out of the car and beat up. Maybe driverless cars are good after all.

Meanwhile these motherfuckers on Fox are 100% trying to get teachers and/or trans folks (both similarly evil under the “groomer” umbrella now as far as they’re concerned) hurt or killed.

Here’s Media Matters:

Fox News has aired 170 segments featuring discussions about transgender people in the past three weeks, with Fox anchors, hosts, and guests incessantly fear mongering about trans people and spreading dangerous misinformation, including the lie that most trans kids “have been led to where they are by adult predators.”

This shit is going to get a lot worse real fast. Maybe the idea they used to push about arming teachers wasn’t so bad after all. Just for different reasons.

Thanks again, Luke! You are a real one. 🙏🙏🙏