Beating it like a dumb beast if it slackens

And with that, the zombie was introduced to America

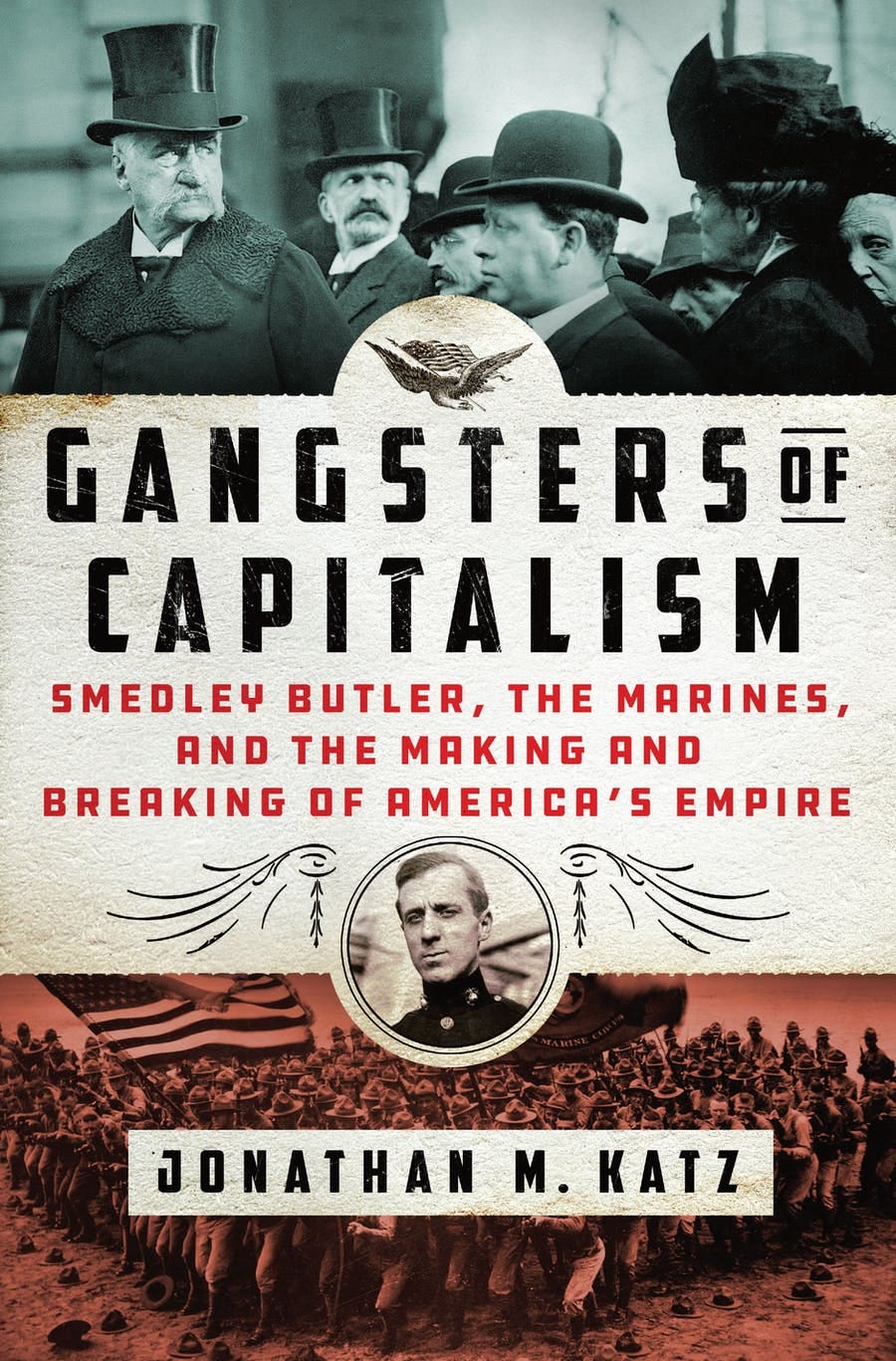

Today we begin in Haiti with an excerpt from Jonathan M. Katz’s new book Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America's Empire.

“For colonizers, zombie stories are powered by fears of revenge or contagion by the people they conquered,” Katz writes. “For the colonized, the zombie retains its older connotations: fear of abduction, assimilation, and losing one’s soul.”

Stick around after that for a roundup of the worst shit of the week that I looked at from me!!!!!

Thank you as always for reading and for your support. If you can afford it at this time please consider a paid yearly subscription. If you do so let me know and I’ll send you a copy of one of my books and you’ll get a free six months paid subscription to Foreign Exchanges by Derek Davidson and Forever Wars by Spencer Ackerman.

Here’s Katz introducing the chapters below:

To write Gangsters, I took on three big tasks: telling the life story of the Marine antihero Smedley Butler, uncovering the hidden history of the rise of America's empire, and tracing how the memories and consequences of that era are still being felt in the places we invaded and conquered. My travels took me to nine countries on two continents, including China, the Philippines, and all over Central America.

That journey also included traveling into the mountains of northern Haiti, where Butler and his Marines crushed an insurgency (known as the Cacos) using tactics of counterinsurgency and ultimately a massacre at a mountaintop redoubt called Fort Rivière. For a time it was rumored that the fort had never existed, then assumed that it had been entirely destroyed. My search for the fort's remains led me to somewhere even deeper than I had expected to go...

I hoped finding the site of the dynamited fort might give me some insight into a place that loomed so large in Butler’s mind. So, in the spring of 2018, I flew to Cap-Haïtien, where I met up with my old friend Evens Sanon, whom I’d worked with closely during my years as a journalist in Haiti. About an hour after leaving the city (and a stop for Evens to pick up cigarettes), we turned onto an unpaved highway. We drove through a riverbed, passing billboards for a USAID project and market stalls selling American rice in bags stamped with the U.S. flag.

For a while, no one we stopped to ask had heard of a Fort Rivière. But as we neared Bahon, a few ears perked up, and soon we were pointed in the right direction. We turned onto an unmarked road into the forest and started to climb the foothills of Black Mountain, until we couldn’t drive any further.

Walking past a group of ti-kay, a style of small wooden houses, I passed children playing with sticks, while the old folks chatted on the big roots of a shade tree. Smoke hung in the air, likely risen from a nearby fire pit where someone was burning wood into charcoal. I spotted a group of people gathered at the entrance to a lakou, a traditional arrangement of ti-kay around a central courtyard. A few were wearing white prayer caps. They looked at me with suspicion.

“Bonswa,” I said.

“Good afternoon,” someone replied in English. “Where are you from?”

The voice belonged to a man who was slightly older than the rest. He was dressed in a silver polo shirt and corduroy shorts, held up by a thick black leather belt. He spoke slowly and deliberately, with a rasp that suggested years of dedication to rum and cigars. “An entrepreneur from the boondocks,” Evens muttered knowingly, so only I could hear.

The man said his name was Ramsey Sanon. (No relation to Evens, as far as we could tell.) He had lived for years in Miami but gave it up to come back to his mountain home. “I’m looking for a natural life,” he explained. Then, as if one thought led inextricably to the other, he added: “There’s not much time left.”

“Until what?” I asked.

“The whole world is going to collapse. But only Haiti will survive. Ogou Fèray said.”